The tendency to measure our worth against unrealistic beauty standards is hardly a new concern, yet it persists even as feminist theory challenges these ideals and media efforts claim to represent diverse bodies. Platforms like TikTok, for example, argue their core values prioritize diversity, with policies that uplift underrepresented communities. Still, self-objectification of both women and men is largely driven by mainstream media (Rodgers, 2015), significantly impacting users’ self-esteem. An increasing body of research emphasizes self-objectification in reported decline of cognitive functioning and is associated with many mental health issues such as depression and eating disorders (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). But with such widespread awareness, why does self-objectification remain so prevalent?

Researchers Corinna Canali and Miriam Doh uncover the “truth” behind the algorithmic structures that construct identities and perpetuate this self-objectification online. Bodies and forms of self-expression deemed as “true,” “normal,” or “obscene,” are not actually objective categories. They are rather social constructs created by institutions who have the power to define them, such as governments, corporations, or tech platforms. One structure that reinforces self-objectification, and distorts self-perception is the use of augmented reality filters. These AR filters have become popular across social media networks that an estimated 90 percent of American young adults visit daily, with 58 percent of teens using TikTok alone (Bhandari & Bimo, 2022). The ways in which these filters, incentivized by algorithmic systems, affect identity, prefer uniformity, and marginalize diversity are explored in Filters of Identity: AR Beauty and the Algorithmic Politics of the Digital Body, co-authored by Corinna and Mariam Doh.

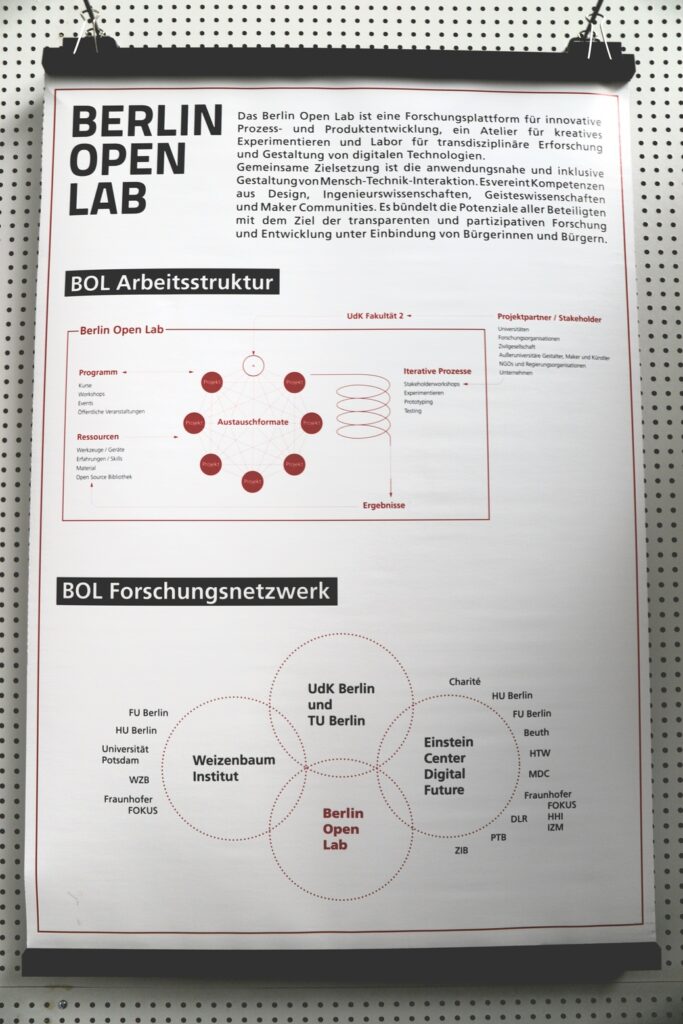

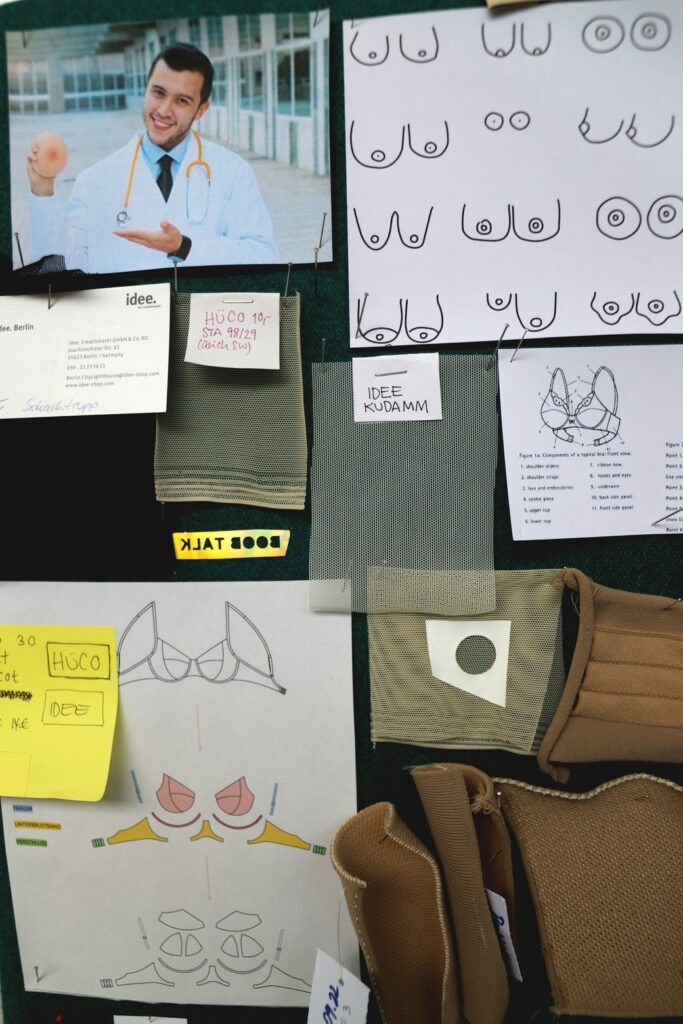

Corinna is a research associate at the Weizenbaum Institute and Design Research Lab, and her project partner, Mariam, is a PhD student with the AI for the Common Good Institute / Machine Learning Group at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. Corinna’s initial inspiration began with a study on nudity in digital and social media contexts. This led to a broader analysis of digital governance engrained “obscenifying” beliefs, where systems are built on the assumption that certain bodies, identities, and forms of expression are inherently obscene. From this, she has developed extensive experience across institutions in examining how platforms and policies act as regulatory infrastructures that shape who is seen, censored, or silenced in digital environments.

In an interview conducted for this article, Corinna discusses how AI-driven beauty filters do more than simply mirror existing beauty norms, but actively construct and reinforce them.

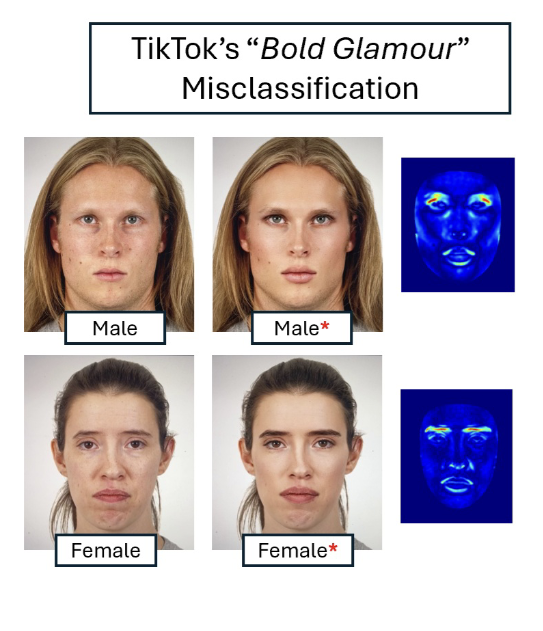

Although TikTok’s effect house policy has been implemented to ban filters that promote unrealistic beauty standards, the platform continues to circulate effects that do exactly that. As an example, Corinna analyzes the Bold Glamour filter, which edits users’ faces in ways that are difficult to detect but tend to favor Eurocentric and cisgender features such as lighter skin, narrow noses, and larger eyes. It also frequently misidentifies or distorts the facial features of certain racial groups. The highest “misclassification rates” were detected in black women, where the filter failed to accurately detect a person’s face or altered their features in ways that don’t reflect their real appearance. This systematic exclusion of non-conforming bodies manifests into a larger trend in technological design, where digital systems tend to perpetuate dominant norms. Bodies that fall outside these norms, including those that are disabled, fat, Indigenous, or Black, are frequently invisible or misrepresented within the algorithm.

Corinna argues that these marginalized identities also have the most underrepresented narratives when it comes to bias in content moderation:

“Also, if you (tech company) own all the means of knowledge, circulation and production it’s quite difficult to allow any other narrative to exist within these spaces.”

She then identifies a serious problem in the subtle ways this discrimination persists unnoticed outside academic circles. She noted that while users may recognize individual instances of bias, they often lack the tools or social power to challenge them within digital spaces.

Notably, the marginalization of these groups has deep roots in the broader historical context of racial capitalism, a system in which racial hierarchies are used to justify and sustain economic exploitation (Ralph & Singhal, 2019). When asked about whether these systems were just reflecting the norms obtained from biased datasets, or if they are actively structured to serve deeper capitalist goals, Corinna describes the influence of deliberate human intervention:

“The algorithm does not work on its own. It works within a system that is constantly being tweaked by real-time content moderation from humans.”

She underlines the active decisions made by people moderating content from policies servicing business and corporate models, ultimately benefitting the platform’s profitability.

The first row shows how the filter incorrectly applies a female-targeted transformation to a male face, while the second row shows a female face altered with a male-targeted filter.

Research shows that frequent use of appearance-enhancing filters is associated with increased body image concerns and higher levels of body dissatisfaction (Caravelli et al., 2025). This lowered self-esteem carries significant economic consequences, with body dissatisfaction-related issues costing an estimated $226 and $507 billion globally in 2019 alone (ibid.). Such widespread dissatisfaction is not incidental but is embedded within the algorithmic logics of these platforms.

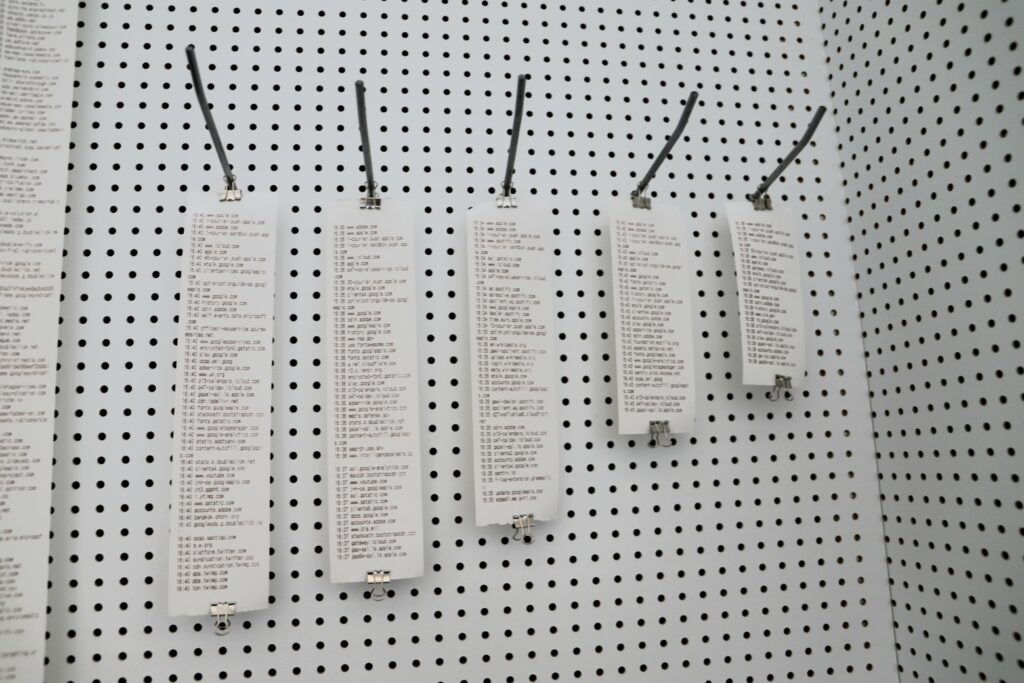

To elaborate, these filters produce idealized versions of the self that adhere to capitalist interests by making users more desirable, and easier to manipulate with ads. One’s face becomes a data point, and their emotions and desires are recognized as commodities. Additional findings emphasize how these automated categorization systems and targeted advertisements actively shape user identity. According to Bhandari and Bimo (2022), the system influences how people construct, perform, and manage their sense of self in ways that benefit the platform economically but may be harmful to the user.

Corinna addresses this when asked whether TikTok truly allows space for authentic self-expression, or if users are instead shaping their identities to align with platform incentives. She feels conflicted, but responds with insight into how the platform promotes self-governing systems, where the primary commodities are users, their data, and their attention:

“When there is this constant negotiation between your own self expression and agency against this corporate logic of profit, it is always difficult to understand to what extent you are actually free to be who you want to be.”

To promote a more authentic version of self-expression, Corinna’s work suggests filters that give inclusive filtering options, allowing users to specifically choose their own aesthetic preferences. However, the persistence of algorithmic bias reveals the challenge of resisting systemic power: even when AR filters are redesigned to reject dominant beauty standards, the algorithm may continue to privilege a certain aesthetic.

Bearing this in mind, Corinna introduces a transdisciplinary approach utilizing design and theory. She describes the nature of this problem as multifaceted and interconnected, necessitating an equally dynamic solution that addresses the whole system. She describes the benefits of design, as her background in visual cultures allows her to embrace visual ethnographic methods to interpret the implications of images for a unique perspective on bias. She says,

“Images are a product of visual tradition that has its own biases outside of technology. Technology has inherited a lot of this bias, discrimination and representation from other traditions that live outside of it.”

In this way, Corinna uses design as a tool to reveal and critique bias. This approach does not require technical expertise, but instead encourages people to recognize the significance of what they’re looking at, and in doing so, begin to see the discriminatory practices embedded within it.

Corinna’s next steps address both the internal complexity of these systems and the broader socio-political contexts in which they function. She offers one possible solution in creating opportunities to rethink and rebuild these platforms, but for this, there needs to be space for alternative systems. Corinna highlights that it is extremely difficult now to access any social network that does not come from big tech companies, because they have created conditions where they hold a near-monopoly over these platforms and infrastructures. The process will require time and multiple layers of reworking, starting with how users are educated about these technologies.

To address the lack of adequate understanding on these issues, she plans to develop tools that promote media literacy by helping users acknowledge what these systems are, how they function, and what their greater societal impacts may be. This perspective would stress the reciprocal relationship between society and technology, emphasizing how each continuously shapes the other.

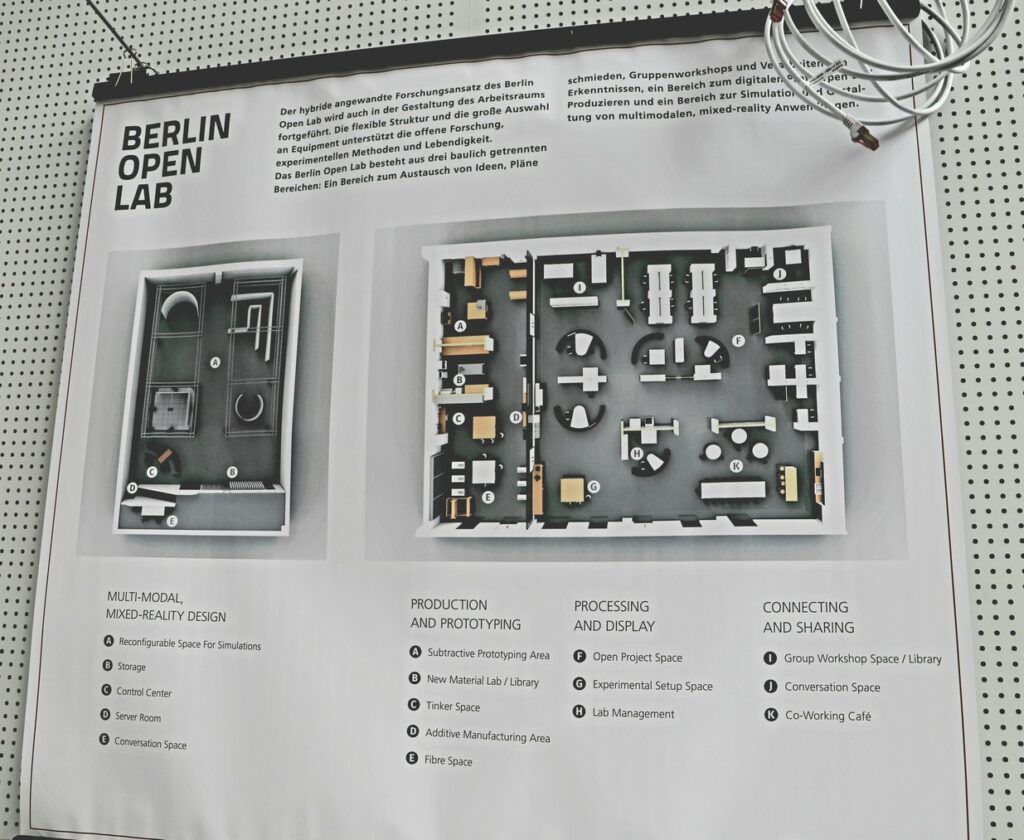

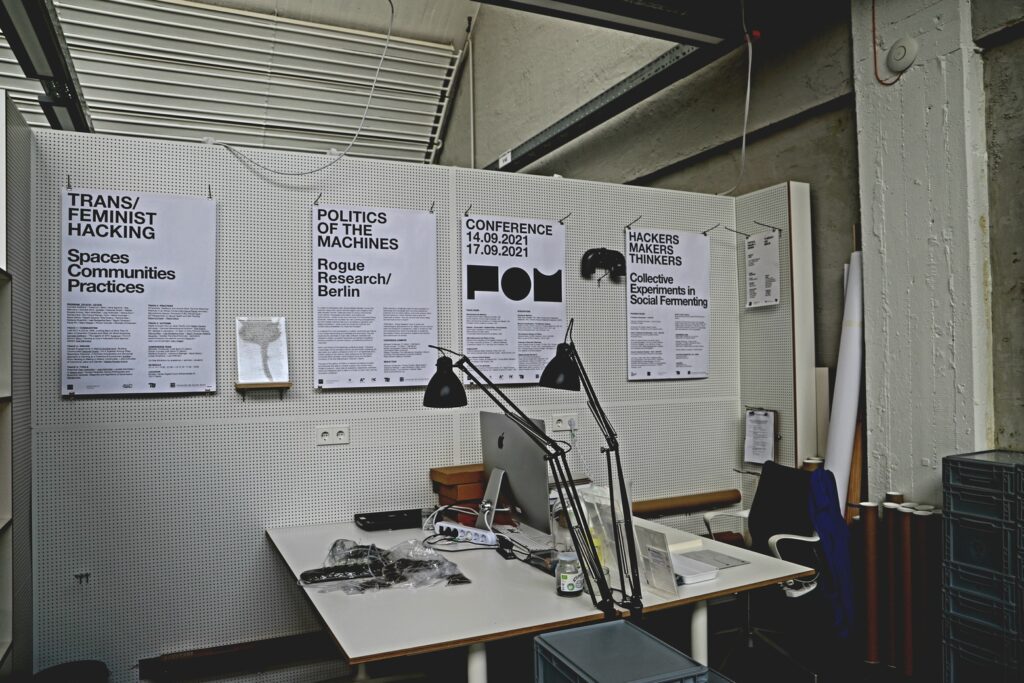

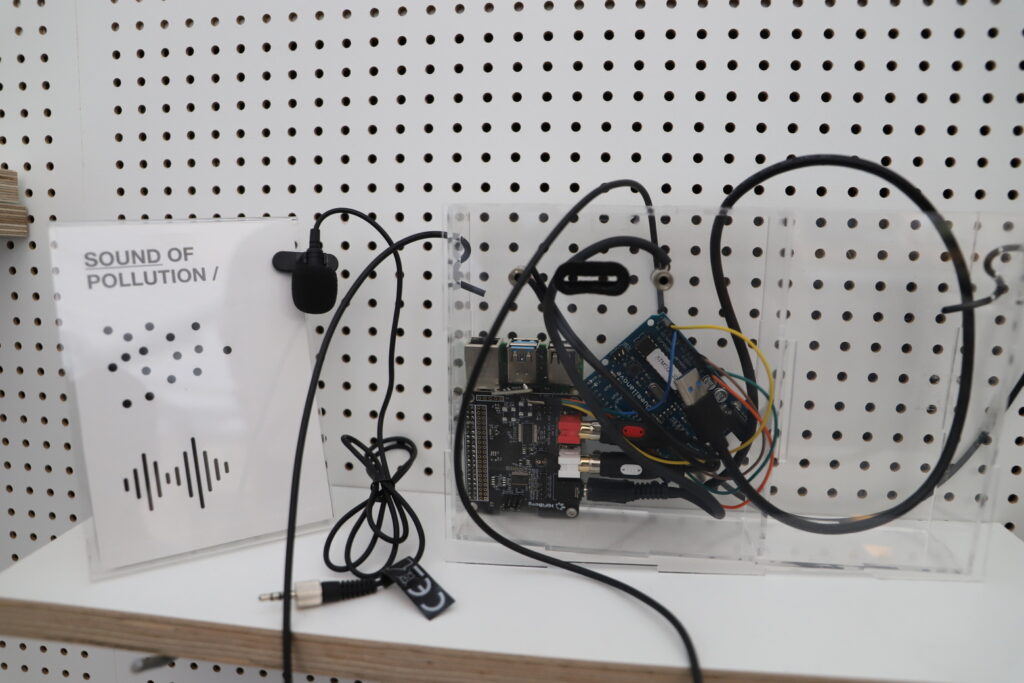

The Design Research Lab and Berlin Open Lab have many projects that explore research through design, uniquely combining critical theory from the humanities with hands-on material production. The lab takes a different path from traditional product design by emphasizing critical reflection on both how products are made and the ways they shape society. Several research projects in this lab consider this approach, including one that addresses the theme of surveillance capitalism discussed here. For a deeper look into how the lab works, check out the spotlight article linked here!