AI applications are growing in popularity, everyday digital tasks are intuitively streamlined, and social media platforms are flooded with automated media that emulate the clarity of actual events. Naturally, this inspires discussions of future opportunities and concerns, such as the possibility of computers overtaking jobs that once relied upon humans. But amidst this consideration of AI into our routine behaviors, how much do we really know about the foundation of these tools? What are the invisible costs of this innovation, and who bears the consequences? The answer is revealed in this article, unsettling accounts behind the scenes of our usage are presented by the data workers’ inquiry.

This community-based initiative fights for fair working conditions and adequate recognition of data workers’ expertise. Since 2022, workers behind AI applications have been investigating their own workplaces to address labor conditions and build workplace power. Derived from the principles of 1880s Marxist thinking, workers conduct research tailored to their political and environmental concerns, with support from trained qualitative researchers. This team of researchers includes lead researcher Milagros Miceli with the Weizenbaum Institute, Adio Dinika, Krystal Kauffman, Camilla Salim Wagner, and Laurenz Sachenbacher. Without compromising the workers’ epistemic authority, they provide training in methods for data collection and analysis to create a methodology for workers to use within investigations. They also diligently monitor ethical and legal boundaries throughout the duration of projects.

The inquiries take place across Venezuela, Kenya, Syria and Germany. Whether in essays, artwork or documentaries, data workers creatively share their perspective working under various AI industries. The striking truths are outlined in the inquiries below. Ultimately, this research will provide structure for collective action, establishing future ethical guidelines in regard to the treatment of data workers.

Venezuela: “Life of a Latin American Data Worker”, by Oskarina Veronica Fuentes Anaya

Native to Venezuela but now residing in Columbia, Oskarina Anaya brings over a decade of experience in freelance data work. As she continues to work for various online platforms, she joined the Data Workers’ Inquiry to advocate for the just acknowledgement and treatment of freelance workers.

Wary of the lack of recognition within her field and to the broader society, she argues for data workers’ entitlement as valuable contributors to technological advancement. Therefore, Oskarina created an animated video to shed light on the daily struggles of data work such as inconsistent working hours, low wages, job uncertainty and unpaid time. Exacerbated by the economic and political crises in Latin America, this video aims to emphasize the structural issues of this occupation that affect many like herself.

In this animation, Oskarina states, “To generate one dollar, I usually need between thirty-five minutes to an hour.”, which demonstrates the severity of her financial strain.

She feels trapped in a vicious cycle: earning less than the minimum she needs to survive, she becomes overworked. Lacking adequate rest, she is frequently ill, leading to additional expenses for doctor’s appointments and medication. With neither time nor money to sacrifice, she continues working, worsening her physical condition. Additionally, Oskarina comments on how invisible her struggle is to the public, explaining, “We are ghosts to society, and I dare say we are cheap, disposable labor for the companies we have served for years without guarantees or protection.” Thus, she hopes this animation will raise awareness into the background realities of these common AI applications.

Kenya: “Data Workers Organizing – The African Content Moderators Union”, by Richard Mathenge

Born in Nairobi, Richard Mathenge is the co-founder of the African Content Moderators’ Union and Techworkers Community Africa. For two years, he worked as a team lead and data annotator. This inspired him to organize a union with his colleagues, aiming to fight for the working conditions of tech workers and content moderators in Africa. His documentary illustrates the traumatizing labor conditions for employees at Sama in Nairobi, Kenya.

Mophat, a content moderator, speaks on his experiences after witnessing content of child abuse and sexual violence. He described his night terrors, commenting, “Such things, they tear up my whole life. First of all it comes with this sense of paranoia… You try to get sleep, but what you read lingers on your mind. In a day you could read three hundred to six hundred texts, and what it has done to you is much more than you could have expected.”

This account was corroborated by other stories of the lasting side effects from long hours of witnessing such disturbing content. Following this, the workers that sought psychological advising to help alleviate their symptoms, found companies were ill-equipped for support. The worker explained that when this consolation was requested, their manager insisted they continue to work as there were too many tasks to complete. If a worker was finally granted permission, they reported psychologists were unable to aid in the management of emotional stress or in related work issues. In essence, this documentary depicts the lack of support in addressing the traumatizing nature of these working conditions.

Syria: “Annotate to Educate: The Dual Life of a Syrian Student & Data Annotator”, by Yasser Yousef Alrayes

From Syria, Yasser Yousef Alrayes is a student finishing his degree in Computer and Automation Engineering at the University of Damascus. He regularly annotates data for projects involved in the development of intelligent digitized systems.

This short film reveals how the insufficient training of Syrian data workers causes a variety of problems, in addition to the low wages and environmental conditions hindering the ability to work. To address this, Yasser advocates for an organized training system that adequately prepares workers for the challenges of the AI industry.

Within this documentary, Yasser describes, “Supervisors play a crucial role in our work. However, without valuable feedback, we end up spending unnecessary time and effort.”

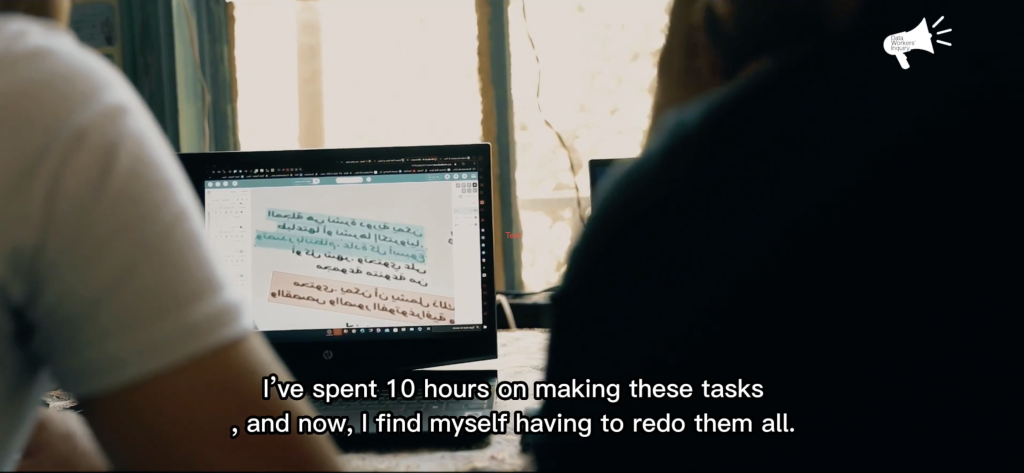

This photo captures a moment of the documentary where ten profitless hours of work are to be repeated. It precisely depicts how data workers often endure extensive periods of unpaid labor, a situation that could easily be prevented with reliable feedback from supervisors.

Germany: “In the Colony of Blooded Eyes: A Trilogy on Working Conditions as a Content Moderator in Germany”, by Sakine Mohamadi Bozorg

Sakine Mohamadi Bozorg is an independent researcher and essayist with an extensive background in Philosophy. She now lives in Berlin where she worked temporarily as a content moderator.

In an essay of three parts, Sakine describes her psychologically scarring experience as a migrant in Germany, working as a content moderator. In the first chapter, Sakine argues that non-disclosure agreements violate human freedom. She compares this agreement to a punishment system from the novelist Franz Kafka’s story, In the Penal Colony. Following this, the third chapter invites Sara, a ceramic artist from Iran, to discuss how constant surveillance within content moderation affected her artwork. In a short film, they reflect on her ceramic pieces, as it is her preferred form of expression, to disclose this experience and defend her previously threatened freedom of speech.

In this short film, Sara and Sakine discuss the emotional manipulation and exploitative atmosphere they face at work, beginning with the hiring process. Sakine observes,

“But based on the job applications that they made, they were telling you that this job does not require any qualifications, in order to not pay you properly… Now, in this way, they are conveying shame to you. That you are doing a job that doesn’t need any quality, any skill, and you are doing this.”.

She informed that this shame was intended to suppress any resistance to such conditions, leaving workers feeling powerless and trapped.

Later, Sakine expresses her interpretation of the ceramic cup Sara crafted. The image depicts the hollow head of a baby, blood stains its eyes and mouth; a metaphor for how she felt after being repeatedly subjected to disturbing content.

Sakine states,

“It had a lot of effects on my mentality, my psyche, and my body. Like during those 7 hours of work, my emotions were changing so many times, I got to the point where I wanted to block all my emotions… I mean to have a head that is empty inside, not feeling anything… Like eyes as a symbol of the information entering and a mouth that is closed because of shame. This is a figure that depicts us in this situation. Showing us in an abusive relationship, which here is a work relationship, and it’s a collective experience.”.

Sara appreciates this interpretation and expands by describing her hopes to visually convey symptoms of exhaustion, artistically symbolizing the experience of many migrant data workers in Germany.

“From Data Workers to Data Workers – Precarious Working Conditions in Content Moderation and their Consequences for Workers”, by Lais, Layla & Omar

In this podcast, content moderators reveal their experience working at Telus International in Essen, Germany. The authors include Layla, Omar and Lais, who have each contributed at least five years to Telus and collectively advocate for more sustainable working conditions. They argue that the lack of psychological support for workers could escalate into a greater issue for the state as a result of the long term consequences to workers’ mental health. Throughout their conversation, they reflect on the frequent experience: exposed to disturbing content and rigorous working conditions, without adequate support or pay.

Due to non-disclosure agreements, their identities are disguised and the record is available in German, with English subtitles.

This interview consistently highlights themes of exhaustion and shame after a day’s work. To elaborate, one data worker avoids disclosing full details of the disturbing content for its indecency, but summarizes the difficult topics witnessed and the nightmares that followed. They also mention there was not a single qualified person able to support their resulting mental struggles. Defeated, they reflect, “And I think you lose a sense of self worth at the job.” This degradation triggered an internal battle, questioning why they tolerate such treatment. However, later in the podcast, another worker asserts, “Without us, social media, as we know it today, could not exist at all.” This contradiction is emphasized in the documentary: despite the necessity of their work to these mainstream applications, workers are regularly exploited and undervalued.

Given the poor acknowledgement of data workers, this podcast ultimately strives to raise awareness and promote greater recognition of the crucial work they contribute.

What can we do?

This research guided by the Data Workers’ Inquiry has paved the way for a just system of employment within AI companies. Now, the influence of the public is essential to reinforcing this effort.

If you are interested in donating to these data workers, please click here.

Additionally, Turkopticon is a non-profit resource led by data workers for the Amazon Mechanical Turk community. It provides a safe platform for workers to navigate which jobs to take, based on reviews of various requestors. This team also strives to improve conditions by confronting their managers with constructive feedback and by petitioning unfair practices. To support their project, please donate by clicking here.

Finally, by spreading awareness to expose unethical practices and by advocating for transparency in methods of data sourcing, we join the movement to end this exploitation.